The Unknown Unknowns of Sovereign Systemic Risk

London, UK - 22nd February 2010, 16:25 GMT

Dear ATCA Open & Philanthropia Friends

[Please note that the views presented by individual contributors are not necessarily representative of the views of ATCA, which is neutral. ATCA conducts collective Socratic dialogue on global opportunities and threats.]

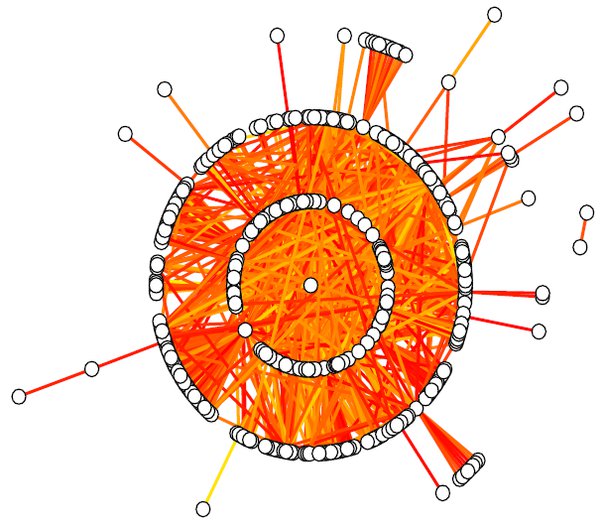

What's the real danger of the Eurozone crisis? The latest unknown unknown to manifest in the global financial markets is the growing potential of sovereign systemic risk. This is a concatenation of individual country risks infecting each other with unknown unknown consequences. Left unchecked, country risk becomes contagious and spreads to neighbouring countries as well as peer groups. Contagion can quickly spiral into systemic risk across a region. Up until now systemic risk arising from banking and financial services has continued to dominate the agenda of most global players -- corporate, government or NGO -- given the long shadow of The Great Unwind and The Great Reset. However, the rising country risk manifest in Eurozone countries, amongst other regions of the world, is increasing the possibility of another type of systemic risk. This is not just financial services related and not centred on banking alone, but actually focussed on sovereign systemic risk, ie, the possibility of sovereign risk default en masse.

Systemic Risk Manifestation

Systemic Risk Manifestation

Country risk is a broad collection of risks associated with investing in a given country. These risks include political risk, exchange rate risk, economic risk, sovereign risk and transfer risk, which is the risk of capital being locked up or frozen by government action. Country risk varies from one country to the next and can become extremely volatile during periods of regional uncertainty as the recent Eurozone situation has begun demonstrating.

. Financial factors such as currency controls, devaluation and regulatory changes; or

. Stability factors such as political dynamics, social unrest, civil confrontation and other unforeseen events;

all contribute to the perception and mechanics of country risk evaluation and build up.

As a result, some countries may end up being perceived to have high enough risk to:

. Discourage foreign inward investment; and

. Encourage foreign funds repatriation.

This impacts the take up of future sovereign debt issues, especially if in parallel, rating agencies keep downgrading that sovereign's ratings and those of entities -- private or public -- domiciled in that country.

From President Obama's unexpected crackdown last month on banks via the Volcker Rule and the European wrangles over PIIGS -- Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain -- to the uncertainty generated by upcoming elections in both the UK and US, the profile of sovereign risk and country risk as an unknown unknown has risen considerably for global investors. Sovereign risk has manifested itself in different ways but most clearly in government bonds, where debt yields have risen for a number of countries, as the perception of that specific risk has increased. However, it is now beginning to meet another big trend -- the return of a clearer, stronger link between sovereign risk and the perceived risk of other asset classes, such as equities and bonds, where the issuing entities are domiciled in that particular country.

How does Sovereign Systemic Risk play out?

Everyone ought to be paying close attention to the troubles in the credit markets of Greece. It may seem hard to believe that the debt problems of a midsize European nation halfway around the world would be of great concern to the rest of the world. Greece, after all, has a population of about 12 million people, which is roughly the same scale as the greater New York metropolitan area. And yet it matters — a lot. Greece has been teetering near default for weeks now. The government has come up with a plan to cut spending and raise its credit worthiness. The plan has gone down very well among European finance ministers, but it has angered people at home, where strikes are becoming common. Plans for even broader strikes are gathering momentum.

Such strikes put Greek cost-cutting plans into jeopardy, which in turn, cause investors to flee other weak sovereign issuers in a similar peer group such as Spain and Portugal. This is contagion. If those countries come under pressure, the stronger economies of Europe, such as Germany and France, are expected to bear the brunt of a bailout. However, their citizens and coalition governments may not allow that. Further, their own exorbitant borrowing needs will likely limit their ability to assist their neighbours. The prospect of higher interest rates and a slow economy are enough to cause widespread pressure on both credit and equity markets around the world. The step by step deterioration in the country risks of the PIIGS can then create a full blown sovereign systemic crisis for the Eurozone, way beyond the banking sector.

In some ways, are the problems in the Eurozone not reminiscent of the state of the markets in September 2008, after the fall of the Lehman Brothers investment bank? That period was marked by extreme volatility and broad declines across virtually all asset classes. The dynamics we are witnessing at present have similar hall marks albeit not so pronounced yet.

What's Incomplete in Risk Analysis?

Though country risk analysis is a well-established field within global risk management, evidence indicates that established measures of country risk are unreliable predictors of actual volatility. Conventional strategies aimed at minimising or otherwise avoiding downside risk are likely to yield limited results at best; at worst, these strategies will mislead managers towards complacency. The unknown unknowns including the unreliability of data and statistics as well as confidence levels are likely to be the greatest during conditions of disequilibrium. Drawing from low probability high impact risk modelling, ATCA proposes an alternative perspective from which to approach country risk. Our perspective is to examine the unknown unknowns for a group of neighbours or similarly positioned countries together -- eg PIIGS -- and then to evaluate the possibilities of contagion across all asset classes for those countries whilst taking into account broader geo-political and socio-economic risk from the big eight: USA, China, EU, Russia, India, Brazil, South Africa and Saudi Arabia.

The most forward-thinking boards have multiple risk specialists and committees so that they can understand all the risks they run. However, aggregating discrete risks together is not a linear sum game, because they have a nasty habit of feeding off each other and creating compound effects. In the present accelerating environment in which collective consciousness, technologies, finance and cultures are fusing into each other, there is a requirement to look at risk very broadly and from the continuous perspective of asymmetric threats, low probability high impact risks and unknown unknowns, known unknowns as well as known knowns. Data and statistics alone can be extremely misleading to prepare for the future and may even prove to be a red herring.

Most of all there is a need to give leadership the confidence to oversee concatenated risks across multiple domains with a long-term perspective. In this context, it would seem prudent to give high level attention to “Low Probability High Impact" outcomes and appoint dedicated risk officers to manage such risks. Co-ordinating risk management solutions is critical so that the possibilities of cross-country contagion can be spotted early on and the adverse fallout from the potential of sovereign systemic risk may be countered in sufficient time.

[ENDS]

We welcome your thoughts, observations and views. To reflect further on this subject and others, please respond within Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn's ATCA Open and related discussion platform of HQR. Should you wish to connect directly with real time Twitter feeds, please click as appropriate:

. ATCA Open

. @G140

. mi2g Intelligence Unit

. Open HQR

. DK Matai

Best wishes